About David Humphreys Miller

About David Humphreys Miller

The following information is from Wikipedia.

David Humphreys Miller (June 8, 1918 – August 21, 1992) was an American artist, author, and film advisor who specialized in the culture of the northern Plains Indians. He was most notable for painting his 72 portraits of the survivors of the Battle of the Little Bighorn. In addition to his portraiture, he was also featured as a technical advisor on Native American culture for the films Cheyenne Autumn, How the West was Won, and the TV show Daniel Boone.[1] Miller also wrote several books on Indian history. In 1948, he arranged the last meeting of the Bighorn survivors at the dedication of the Crazy Horse Memorial.

Biography

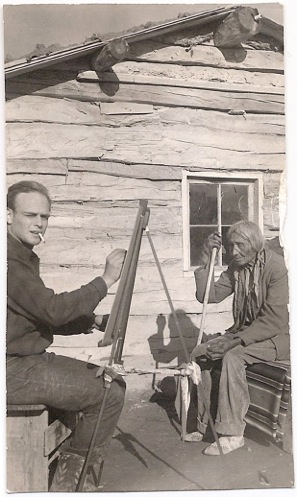

Miller was born in Van Wert, Ohio, into a family of artists.[2] He spent most of his childhood sketching and painting to develop his artistic talent. At the age of only 16, and with the aid of a translator, he first visited the Pine Ridge Reservation of South Dakota and began interviewing the remaining survivors of the Battle of Little Bighorn, most of whom were over 70 years old.[3] Most of them had never before conveyed their stories to a white man. As the Indian warriors were a majority of the battle survivors, these assorted interviews proved very important to later historical study of Custer’s fall. He went on to study art at the University of Michigan, New York University, and at the Grand Central School of Art under Harvey Dunn. He also worked privately with Winold Reiss, continuing his work on the Bighorn survivors with his family’s blessing during the summer.[2] In 1942, he went into service for the 14th Air Corps in China during World War II. By the time of his return to the United States, there were only 20 living survivors of the battle. Furthering his study of the Plains peoples, Miller learned 14 Indian languages, including sign languages, and was adopted into 16 separate Indian families.[2] Eventually, he was given the name Chief Iron White Man by Black Elk, in honor of the Oglala Sioux medicine man who had been at Little Bighorn. He later served as a technical advisor for 25 “Western” films. A good friend of Korezak Ziolkowski, Miller organized the last reunion of the remaining 8 Bighorn survivors on June 3, 1948, at the dedication of the Crazy Horse Memorial. In 1971, he wrote an extensive article on the recollections of the Custer survivors for American Heritage magazine.[4] In his later years, Miller and his wife, Jan, lived in Rancho Santa Fe, California, where he continued to paint and write until his death in 1992.[2]

Works

Miller’s most prominent and historically significant works were his 72 portraits of Custer survivors, which began with his painting of Chief Henry Oscar One Bull in 1935, and were completed in 1942. Most of his portraits were painted on flat, white acrylic.[5] He took special care to precisely recreate native gear, clothing, and weaponry. In 1972, his works won the Western Heritage Award from National Cowboy Hall of Fame.[6][page needed] His other works included the mural commissions of Mount Rushmore, and at the Citadel, Charleston, South Carolina. His writings included the books Custer’s Fall: The Indian Side of the Story (1957), and Ghost Dance (1959).

A Personal Statement

By David Humphreys Miller

from Brand Book Number Six, San Diego Corral of the Westerners

(San Diego, 1979) Art has been said to be an intense form of individualism. Thanks to my stubborn disposition and certain inherited creative impulses, I began my Indian research in 1935 when I was going on sixteen. My high school history books somehow seemed lacking in their biased treatment of the Indian Wars. It was fifty-nine years after the 1876 Battle of the Little Big Horn – Custer’s Last Stand – the apogee of Indian-white conflict. I calculated that some Indians might still be alive who could tell me their version of the Custer Fight.

With my parents’ blessing – both were artists – I traveled West from my Ohio boyhood home to Sioux and Cheyenne reservations in the Dakotas and Montana. George Armstrong Custer, too, had grown up in Ohio, had played Indian much as I had, and had found his destiny in the West. I was determined to dog his trail.

I recall feeling a considerable sense of urgency when I began my quest. Will Durant has written that “no man in a hurry is quite civilized.” I was anything but civilized in my haste to find as many old Indian veterans of Little Big Horn as I could to straighten out history. The Indians almost certainly had never even heard of Durant, yet I found there was no way of hurrying them. The project of seeking them out, persuading them to pose for their portraits, and interviewing them about their individual roles in the Custer Fight took a number of years – 1935 through 1941 and 1946 through 1955 when the last survivor died.

While I had no reason not to believe their personal testimony, this was an era before oral history had quite come into its own as a completely reliable source. Thus I felt compelled to check and cross-check the data – against the gratuitous military records contrived for the benefit of Custer’s widow and, no little, for the salving of the Army’s pride in having lost both battle and campaign. Little help there, at first – in fact, a contretemps on the time angle.

My informants among the Indians agreed that the battle had started at noon—when the sun was overhead. Yet military accounts stated clearly that Reno’s attack on the south end of the great encampment had occurred shortly after 3:00 on the afternoon of June 25—a discrepancy of three hours. Only after considerable research did I learn that in 1876 there were no time zones across the country. The Seventh Cavalry, although more than 1500 miles west of the Windy City, was fighting on Chicago time!

The language barrier was probably the greatest. It took time and doing—about a year-and-a-half to learn Sioux, then the other unrelated tongues. I relied on interpreters early on, then, despite my confidence in and friendship for them, I gradually came to believe in a more direct approach. None of the old-times spoke or understood English. It was up to me, I reasoned, to figure out how to ferret into their minds by knowing their means of communication. With all respect to the interpreters, I realized their temptation to color translations with their own preconceived notions or earlier-gathered stories. It narrowed down to direct communication with each of the Little Big Horn survivors, as well as a good many other veterans of various Indian-white engagements.

At that time no Indian language vocabularies or grammars were available to me. So I gradually built up my own phonetic systems until I acquired fluency and could dispense with interpreters. It turned out to be a significant step in that I gained both much clearer understanding and improved rapport with my informants. Sound recorders of that era, by the way, were bulky and expensive; moreover, I was usually miles from electric outlets. So I relied entirely on my own hand-written notes—often taken down as the Indians spoke, then later translated into English. In many cases, I was able to arrange repeated interviews with the same informant, checking details and making new portraits.

In the earlier years I sketched the portraits in colored pencils on tinted art paper. Later, I used pastels and tempera over an initial drawing in Conte crayon or pencil. Later still, at my father’s urging, I painted only in oils—the least fragile and most permanent of media, although it involved carrying more material and bulkier equipment into the field. I learned to underpaint the faces in green earth, imparting cool tones to offset the Indians’ rich copper and brown coloration.

Since I wanted the features to have maximum impact, I painted many of the portraits on flat, white acrylic backgrounds, often eliminating shoulder. I omitted necks as well, unless the Indian wore a distinctive necklace or other special ornamentation.

In larger portraits, such as those reproduced in this book, I have incorporated head and shoulders, complete with ceremonial costume, against a colored background. Items of costume, by the way, are from my personal collection, nearly every article of which was given to me by my Indian friends. John Sitting Bull presented me with the war-bonnet and breastplate depicted in my portrait of him included here; the porcupine quillwork on the head-band and breastplate involved many long hours of painstaking work to achieve the proper texture.

There were even greater gifts of friendship. Black Elk, legendary medicine-man of the Oglala Sioux, central figure of John G. Niehardt’s famed book Black Elk Speaks and a veteran of both the Battle of the Little Big Horn and the Ghost Dance uprising, adopted me as his son in 1939. In an adoption ceremony in the Black Hills, he have me the name Wasicun Maza (Iron White Man). As an adopted relative, as well as a trusted friend, I enjoyed unlimited entrée into Indian circles the country over.

Black Elk instructed me in the religion of his people. Through him I came to learn a great deal of the workings of the Indian mind and spirit and gained an appreciation of the Indian sense of values. I feel this knowledge has been vital in portraying these first Americans.

Whether it involves painting Indians or cowboys, mountain men or stagecoaches, Western art entails meticulous research and the most patient fidelity to detail on the part of the artist. Connoisseurs of the genre are highly critical of the slightest historical or technical inaccuracy. Nothing can be faked in terms of correct gear, clothing, or weapons—not to mention the artist’s usual considerations of composition, color, tone and anatomy.

Any artist contemplating entry into the field would do well to ground himself thoroughly in Western lore—until he is even more expert than any prospective collector. All too often, would-be Western artists make the mistake of copying old photographs or the works of such masters as Remington or Russell—dead giveaways to the sophisticated. With a firm underpinning of direct knowledge of the West, one simply has no need to borrow from those who have blazed the trail. Save for figures in an action canvas, I have been careful to avoid painting mere Indian types. I have had the opportunity to know personally thousands of Indians—each of whom I sketched and/or painted from life and, I am proud to say, regarded as a friend.

I had the good fortune to study Indian portraiture under the late Winold Reiss, famed for his pastels of Blackfeet Indians, and Western action painting under the late Harvey Dunn. In recent years, I have enjoyed the treasured friendship and inspiration of Olaf Wieghorst—acknowledged dean of living Western artists and a fellow Westerner in the San Diego Corral. Moreover, I have been blessed with an indispensable help-mate—my wife Jan—whose considerable talent in both art and writing have provided me with extra sets of eyes and brains—assets no professional artist should be without. Her fresh eye has often “saved” a painting of mine from certain destruction, and she is a veritable sounding board for my manuscripts—including those in this book.

My father used to say, “A successful work of art is 2% inspiration, 98% perspiration”—meaning that such achievement is pretty much simple hard labor. Waiting to get into the mood for painting is foreign to my routine.

I was taught to stand at the easel to insure the utmost vigor and energy output. My work, I hope, reflects it. Standing also affords me a readier means of gauging the impact of a painting at various distances. Working at a daily rate of eight hours, I decline taking off weekends or holidays, and have no desire for vacations. I have traveled the world over, I have seen all I truly wish to see, and my youthful wanderlust has wanted. In no way do I intend a sense of smugness. Most artists agree that their learning process never stops. I trust my own self-education and, perhaps, the achievement will never cease.

Read more: http://amertribes.proboards.com/thread/568#ixzz3GpW8eFPc